Writes Allan Golombek a Senior Director at the White House Writers Group for Real Clear Markets.

The scene in the Hamburg supermarket was stark. Row after row of empty shelves, dotted by a few products made domestically. Edeka supermarkets, the largest supermarket chain in Germany, emptied one store of every last imported good on a weekend. They were making a point. Rather than a protest against openness and diversity, it was an object lesson in the benefits we all derive from those two values. It was a defense of tolerance, but also a reminder that openness to goods and services, people and ideas is not just something we engage in to help others, but to help ourselves, directly and every day.

It is not surprising that this case for openness was made in Hamburg, a city that used to serve as a major port of departure for German immigrants to the United States, and the place widely believed to be responsible for the development of the hamburger, one of many foreign dishes that achieved enormous international popularity. Stripping the shelves of foreign-made products didn’t just demonstrate the advantage of drawing people from around the world through liberal immigration policies, as valuable as that is. It also illustrated the indispensable advantage of being free to import, utilizing resources and skills that can be found around the globe. While pro-trade politicians often try to sell free trade as a way of encouraging exports to create jobs, far more important is the fact that it makes it possible to import, enhancing choice – which is the economic purpose of working in the first place..

The ghost town image of the Edeka supermarket helped make it clear just how much we benefit from imports, of food and other goods, and how important they are to us. In the United States, the amount of imported food continues to increase as Americans consume more products that are either not locally available or not grown fast enough to meet demand. Americans import a wide variety of foods, literally from fish to nuts. Some are not grown in the United States, such as bananas and coffee. Many are made a lot more cheaply in other countries. Many are seasonal, and many new entirely to Americans (as pizza, bagels and felafel once were). Rather than a source of economic decline, two of the driving forces behind the growth of food imports are the desire to cut back on the cost of one’s food budget, and rising incomes spurring a wider desire for choice. Next time you sit down to a meal or grab a snack, ask yourself if it would be available to you if it wasn’t for global trade. No lamb from New Zealand, salmon from Norway, or pasta from Italy.

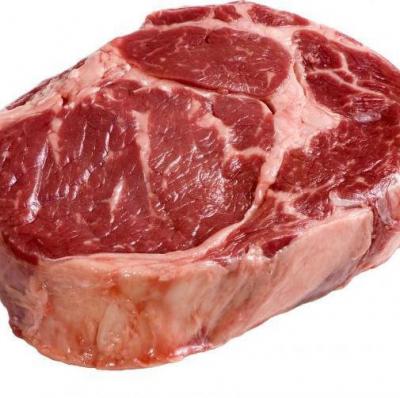

And next time you hear a politician criticize NAFTA, bear this in mind: The two largest sources of agricultural imports to the United States are its trading partners, Mexico and Canada. That includes most sugar and tropical products, such as coffee, cocoa, and rubber, and animals and animal products, including beef and veal. If your doctor has told you to eat your veggies, bear in mind that Mexico dominates vegetables imported into the United States, supplying peppers, cucumbers, tomatoes, corn, pinto beans, broccoli, and cabbage to name a few. Canada supplies carrots, cauliflower, asparagus, mushrooms and potatoes. NAFTA is good for you, physically as well as economically. And if you’re worried about the trade deficit with China, bear in mind that it includes billions of dollars worth of seafood each year, including farm-grown tilapia, shrimp, salmon and catfish.

The value of eating globally, not locally, undermines the core arguments of a growing anti-trade movement: Locavorism, which is based on the flawed premise that a diet of locally grown food offers environmental, economic and social benefits. In fact, the opportunity to import food extends our food supply chain, enhances competition and choice, delivers lower prices, and provides greater variety – the spice of life, literally as well as figuratively.

Over the years, we have been shaping a global diet. The brief removal of imported food from a supermarket’s shelf in Hamburg demonstrates its economic and cultural value to us.

Allan Golombek is a Senior Director at the White House Writers Group.

| A RealClearMarkets release || August 25, 2017 |||